Dumpling launches to make anyone become their own Instacart

Gig economy companies like to tout the flexibility and freedom they offer workers, but for the people finding work through companies like Instacart, Uber, DoorDash and Lyft, the economic and physical risks can outweigh the rewards.

Contractors who are now considered front-line providers of essential services for their wealthier customers in the age of social distancing brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic have struggled with lack of benefits, lost tips and wages, and a dearth of back-end support.

Dumpling, a startup in the food delivery space, was born to challenge the status quo in the gig economy by giving more ownership to the workers that power it. Dumpling connects shoppers to all the resources they need to migrate off the Instacart platform and start their own personal-shopping business.

Dumpling is launching with a focus on food delivery, as the pandemic has transformed the perk into an essential service for home-bound citizens. So far, it has enabled more than 2,000 shoppers in all 50 states to become their own personal Instacarts.

Dumpling co-founders Joel Shapiro and Nate D’Anna met in college and were looking for a way to work together. Shapiro and D’Anna ditched their corporate jobs at National Instruments and Cisco, respectively, to create Dumpling.

“[We thought] what if we actually create a company to solve their problems and not just the one percenters hanging out on the coast?” D’Anna said

Before we get into how Dumpling works, let’s discuss the obvious: Not every gig worker wants to be a business owner, which is exactly the opposite of what the startup needs to succeed. Despite the gig economy’s proliferation over the last decade, only 3% of adults said they performed gig work as a primary source of income; fewer than 1 in 10 adults were full-time gig workers, according to the Federal Reserve’s latest report.

Instead, a larger issue within the gig economy is classification of workers, leading to the rise of unions and co-ops for more shopper support.

Dumpling is another example of what the future would look like.

Shapiro admits that not every gig worker will need Dumpling. But instead of pitching Dumpling solely as a place for gig workers to start their own businesses, he thinks the startup can bring more money into workers’ hands.

“With multiple years of all these multi-demand apps, we know that workers are going to be exploited and screwed at some point and their pay is going to be drastically reduced,” he said. “We’re trying to make them ultimately have control so the rug can’t be pulled out underneath them.”

How it works

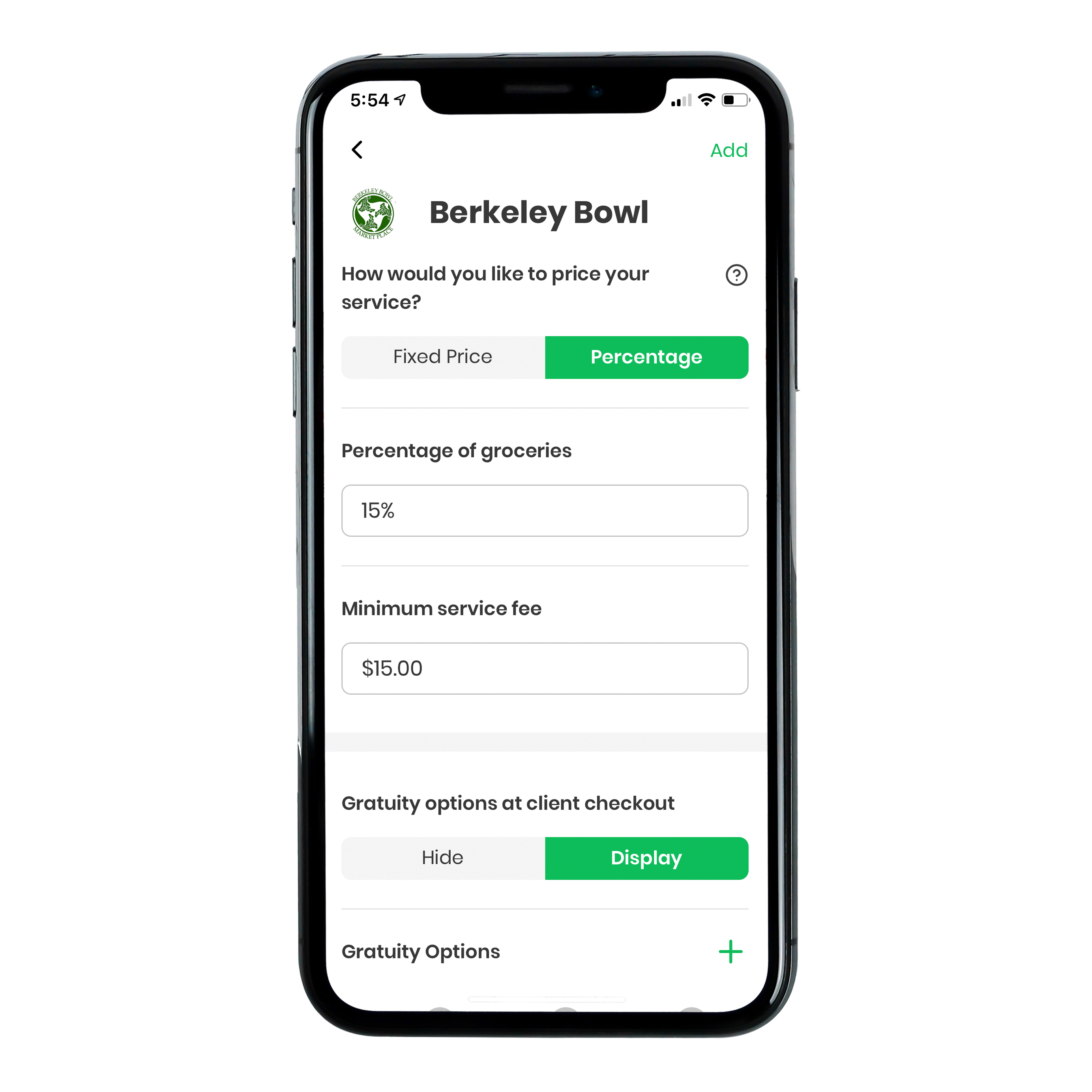

To start, Dumpling helps users create their own LLCs. Then it offers a slew of different products, including a Dumpling credit card to help shoppers buy groceries before customer payment, an app to help centralize deliveries and customer communication, and a forum for mentorship and worker support.

Image Credits: Joel Shapiro / Dumpling

Shoppers primarily acquire customers through marketing and self-promotion when dropping off orders for other delivery apps, according to Dumpling. Some customers have recently started going directly to Dumpling to look for shoppers to order from in the area.

Dumpling gives 100% of tips to business owners. Unlike Instacart, Dumpling allows business owners to pick what tip options show up for their customers and set a personal default tip minimum. There is also space for customers to leave reviews.

The company makes money in a few different ways. It charges shoppers a one-time $10 fee to set up, which includes a Dumpling credit card, a listing on the website and a shopper search tool. The platform then charges shoppers either a $39 monthly fee or a $5 per-transaction fee for each time they book a job. On the other end, customers pay 5% on top of orders for payment processing.

Dumpling claims it can help shoppers make three times as much money as Instacart shoppers. But let’s do the math.

While the monthly fee or $5 per-transaction fee could eat into tips, Dumpling claims that users make $33 in average earnings per order, which is three times as much as Instacart users. Instacart estimates that full-service shopper pay ranges from $7 to $10 per order, according to a NerdWallet article.

Because shoppers can set their own rates, customers could simply flock to the cheapest option of the day, thus driving competition between shoppers to keep rates low (and make less money).

There are a few reasons why Dumpling doesn’t think it’s going to be a race between shoppers.

First, Dumpling customers are largely repeat clients who crave a personalized shopper to help them out. This repeatability gives shoppers some flexibility and stability, income-wise. Shoppers can schedule weekly grocery delivery times so they can manage the orders, instead of trying to drive an Uber and maximize their time on the road.

Second, Shapiro hopes that pricing isn’t the only reason a customer goes to a shopper. He noted that reviews and ratings are big sells, as well as areas of focus like vegan, local farmers’ markets, dietary restrictions and special diets. Imagine if you’re newly joining Keto and you can get a Keto-savvy shopper to pick up ingredients for you, in other words.

In the past three months, the platform has brought in tens of thousands of reviews on shoppers. The average rating of a Dumpling shopper is 4.9 to 5 stars.

It can’t fix what is broken

Even though Dumpling wants to bring ownership to the gig economy, it is experimenting with ways to support its growing network. One way would be getting bulk discounts on health insurance and benefits. Soon, Dumpling is starting a fraud protection benefit for any shopper on its platform.

While Dumpling can’t fix the gig economy, it can drastically change the way that the people within it work and own their career. Especially those few who rely on the gig economy as their sole job.

Matthew Telles, one of Instacart’s first shoppers in Chicago, fondly remembers the grocery delivery platform’s early days. He would average 20% tips on all orders, rarely drove more than five miles for a delivery and was even invited to staff engineering calls to give feedback on the platform.

Then Amazon bought Whole Foods, a deal which Telles thinks pressured Instacart to get the biggest market reach as quickly as possible (which included saving money). He received orders from all over the state. Instacart threatened to take away tips. The engineering call invites stopped.

Five years later, Telles remains on the app to advocate for shoppers. His efforts have contributed to millions in settlement payments from Instacart. The company, which has risen to a level of prominence during the pandemic, recently turned its first profit. Its shopper network continues to complain of lack of support from the platform, and has organized multiple times for better wages, changing default tip minimums and personal protective equipment.

“Fighting Instacart is my hobby now,” Telles said. “Dumpling is now my career.”

Dumpling did not disclose profitability, but said order volume has spiked by 20x. The unprecedented growth has led Dumpling to recently announce it raised $6.5 million in Series A funding, led by Forerunner Ventures. Participating investors include Floodgate and FUEL Capital. The company’s total known venture funding to date is $10 million.

As for Telles, he loves the flexibility he can have to pick up a gratitude meal for the most consistent customers along with their groceries. He’s cut his hours in half and doubled his income by going full time on the app. And, to his delight, he’s been invited on calls with Dumpling’s co-founders themselves, similar to the early days of Instacart.

No comments: