WeWork’s S-1 misses these three key points

No startup is as polarizing as WeWork, and for good reason. The company, whose relentless growth has seen it open 528 locations across 111 cities in just about nine years, has never been entirely forthcoming on exactly how the unit economics add up at its locations. And so we have had a beautiful Rorschach test for the financial class these past few years regarding the company: it’s either the greatest financial return of all time or a Ponzi scheme (and absolutely nothing in between dammit).

That ambiguity is supposed to change with the company’s S-1, where it is required by law to show a reasonably comprehensive set of numbers to investors in order to go public. Unfortunately, despite all the verbiage (“Our mission is to elevate the world’s consciousness.”) and data, we still don’t know the health of the core of the company’s business model or fully understand the risks it is undertaking.

Here are three questions that remain unanswered so far by the company’s filing.

No cohort data on contribution margin

As I pointed out a couple of months ago, the ability for investors to understand the true unit economics of WeWork’s business is critical for cutting through the debate over its financial future.

It’s not as though WeWork hasn’t tried to give us some insight in its S-1. One of WeWork’s core operating metrics is “contribution margin including non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost” (or what I will abbreviate just this one time as CMINCGAAAPSLLC). Through this metric, the company offers us a single number into the health of its business — essentially a way for investors to understand the performance of the company’s mature office locations.

This metric is reasonably complicated given the complexity of WeWork’s business. For instance, the company has to build out new spaces and fill them, which is costly, but is also a one-time expense that shouldn’t affect the financial performance of the location over time. There is also the consideration of how to handle free rent in the early years of a lease and rent increases in the later years that comes with being a tenant of a building (that’s the “straight-line lease cost” part of the metric).

The company has set a target contribution margin of 30% for mature locations (defined as those locations open for at least 24 months). It’s been hovering around 27% for much of the past few years, with a slight dip in the second quarter of 2019 to 24%. Regardless, this sounds reasonably good in a sort of pure “hand-wavy” way.

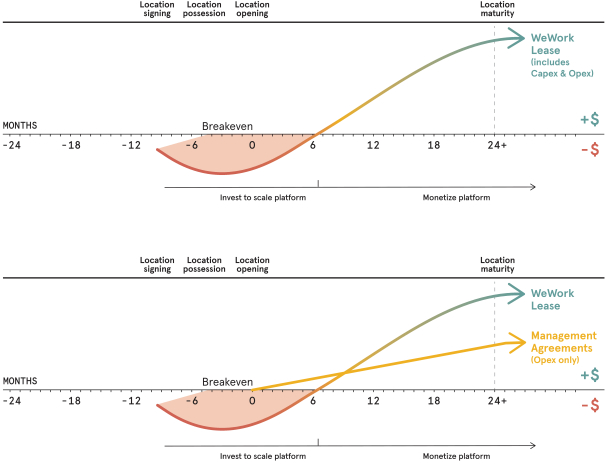

What’s missing here though is that WeWork has aggregated its finances for hundreds of locations down to a summary statistic, complemented with a huge amount of text devoted to describing the evolution of a property from lease signing to mature profit-making office. At no time does the company describe the contribution margin and how it changes throughout the course of a single lease. Instead, it provides the following completely numbers-free chart showing that … it makes more money as time goes on.

Via WeWork’s S-1 Filing

How is margin changing at its older locations? How is margin changing as it opens up in places like India, with very different costs and revenues? How do those margins change over time as a property matures? WeWork spills serious amounts of ink saying that these numbers do get better … without seemingly being willing to actually offer up the numbers themselves.

The declining fortunes of international WeWork

WeWork might have started in New York City, but it is absolutely a global company. According to the S-1, “over 50% of our members are located outside of the United States as of June 2019.” Those locations can be quite successful; London, for instance, has an occupancy of 93%. Growth is continuing at a staggering rate. The company’s greater China revenues increased more than 300% and 270% in non-UK/China foreign markets year over year to 2019.

That’s an exciting story, but this is also perhaps where WeWork was the least transparent in its prognostications for the future of its business. In its market sizing section of the S-1, it says that “When applying our average revenue per WeWork membership for the six months ended June 30, 2019 to our potential member population of 149 million people in our existing 111 cities, we estimate an addressable market opportunity of $945 billion.”

Yet, the revenues from those expansion locations are a different story. WeWork itself admits this, writing “For example, average revenue per WeWork membership has declined, and we expect it to continue to decline, as we expand internationally into lower-priced markets.” Indeed, according to the footnotes, the numbers must be so bad that it actually excludes India memberships from its average membership revenue (“in each case for the six months ended June 30, 2019, and in each case excluding WeLive and IndiaCo”).

That might be one reason why despite its rapid international growth, WeWork has only reduced its revenue concentration inside the United States from 62% to 56% over the past year.

The missing information here is the number of memberships by country — a set of numbers that I couldn’t find anywhere in the S-1. Without some comparison of average revenues by country, there is no way to determine whether the “addressable market opportunity of $1.6 trillion” is in any way realizable by WeWork.

Anti-corruption and anti-money laundering controls

Construction (and vicariously, real estate) are among the most corrupt industries in the world. In New York City, corruption in interior construction — like the build-outs that WeWork has to perform when it signs a new lease to prepare an office building for tenants — have been described as “commonplace.” Unlike software platforms that can exist in the cloud, owning and operating real estate can be a very intricate and complicated business.

And so as I wrote a few months ago, “Real estate is a messy and occasionally corrupt business, and as WeWork has soared to become the largest landlord in New York City, its compliance and risk mitigation is extremely critical to its long-term sustainability as a public company. The range of disclosures here can be as simple as a short risk factor, to what I would expect to be something more substantial.”

Well, all I got was a risk factor, and this remains a gaping hole.

In its risk section for international expansion, WeWork says that one of its risks is “corrupt or unethical practices in foreign jurisdictions that may subject us to compliance costs, including competitive disadvantages, or exposure under applicable anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws.”

Worse, WeWork is particularly brazen in the company’s lack of control over the issue. Here’s the text describing its mitigation: “Under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (the “FCPA”) and similar anti-corruption laws and local laws prohibiting certain corrupt payments to government officials or agents, we may become liable for the actions of our directors, officers, employees, agents or other strategic or local partners or representatives over whom we may have little actual control.” (My emphasis added).

I get that this is legal boilerplate in some ways, but for a company that literally has to handle corruption on a day-to-day basis, I expected more than, well, we can’t control anything anywhere ever.

There’s a lot to like in the WeWork S-1, but these three information gaps (among many others I haven’t gotten into) make it challenging to dissolve that financial Rorschach test into better analysis.

No comments: